The resource abundance in the US of the past decade came from the relentless drive to perfect the application of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques. Operators and service companies now have a very good handle on these upfront inputs, but it still seems that no one truly understands how to manage all the outputs.

Water can be considered a waste stream of the oil production process, and this waste stream is made worse by several factors: unconventional wells tail-off oil production quickly (leading to increased water-to-oil ratios), the existence of a significant base of water production already in place due to wells drilled during previous oil booms, and the high variation of the quality of the produced water. Indeed, waste-water is contaminated so management is not just about transportation or storage but also treatment.

To be clear: produced water really is the issue, and these volumes absolutely dwarf the upfront water needs for drilling and completions: due to the high decline rates of unconventional wells, the more oil the US produces, the more it must keep producing just to stay level, and this only means more and more produced water.

To put the water issue in perspective, a typical well in some of the most productive basins could have an initial water-to-oil ratio of 2:1. By around year four this could increase to 4:1, doubling the amount of produced water per well in only two years; for legacy wells, this ratio could be as high as 10:1. In our June 2019 WaterIQ report we estimated that in 2019 wells in the US will generate 18.6 billion barrels (bbl) of water, up almost 5% from 2018 alone. We project that produced water will increase to 23.6 billion bbl by the end of 2024, a nearly 27% increase…and that’s only under our “base case” assumptions! For 2019, we estimate drilling and completions requirements to be 4.6 billion bbl, just shy of 25% of produced water.

This is significant because for years, going back to the beginning of unconventional resource production, the focus was understandably always on the upfront water needs: faced with high well costs, operators were concerned with getting resources to market as fast as possible. Now that there is a considerable, established production legacy, operators are fully realizing the extent to which produced water is not only a sizable issue, but an ongoing, essentially perpetual, one.

Produced Water – It’s Not Just a Permian Problem

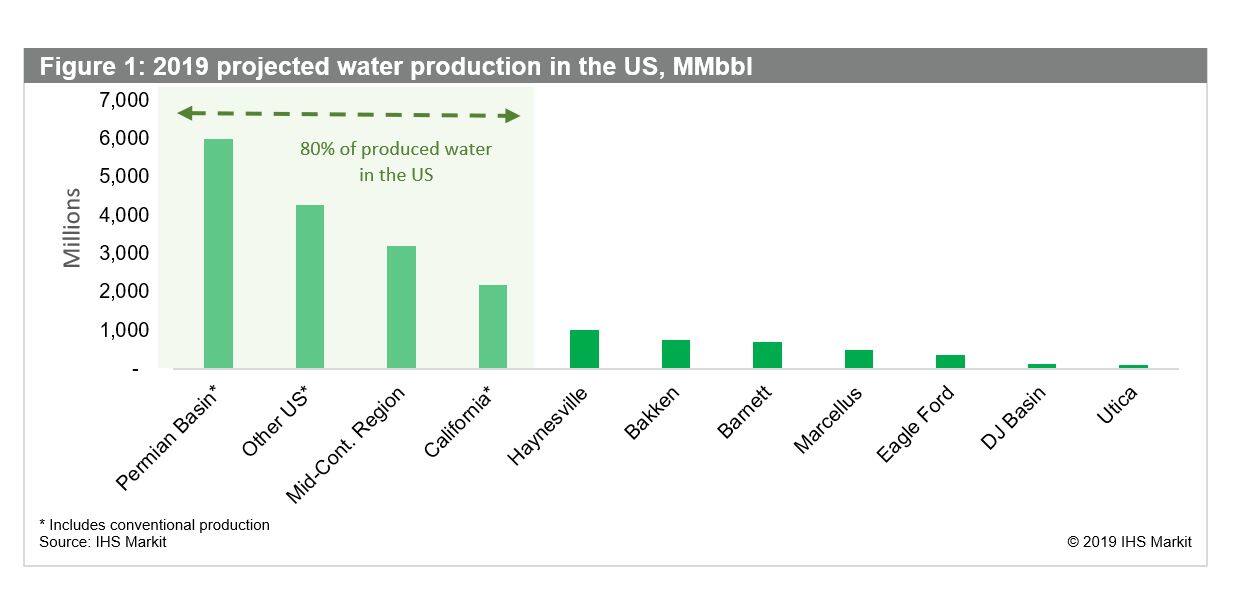

You already know that the Permian influences total water production greatly, but the attention paid to West Texas masks the reality that other areas also contribute materially to the produced water issue. Figure 1 shows just how diffuse US water production is.

Figure 1: 2019 projected water production in the US, MMbbl

In such a Pareto distribution, one would normally expect a roughly 80/20 split, whereby 80% of the problem is caused by 20% of the groupings (implying you can mostly solve the problem by making relatively few adjustments), but our data shows that’s just not the case here. Indeed, we’re faced with a more even, roughly 80/40 split, so the US faces the challenge of trying to address a common problem in a geographically fragmented market.

Without presuming that we can completely forget about areas with mostly conventional production, we can fairly say that the solutions for produced water are much more apparent there. By nature of being conventional, the reservoirs are well suited to re-injection and waterflooding, so while produced water is high, the need for solutions is not as acute as in newer areas of unconventional production.

Since it occupies the second spot, we must mention “Other US”. We don’t break this out because we approach our research from a hydrocarbon perspective, and oil & gas production from these regions really is insignificant since they are primarily legacy plays. Nevertheless, a history of vintage production means low oil cuts and high volumes of produced water, leading to the placement you see in the chart.

That leaves the Permian, the mid-continent region, and the Haynesville as the top water producers from unconventional assets, with the Permian alone projected to account for 32% of the US’s produced water by the end of 2019. These areas are now well-defined on the macro-scale, in a sense their geographic and geological boundaries are mapped. This masks the fact that on a well level, production in these areas can be very de-localized, proving that the truism “location, location, location” most often associated with the real estate market holds also for water management.

To the water market, we can assign a further “3L”s.

Location, Location, Location and…Logistics, Logistics, Logistics

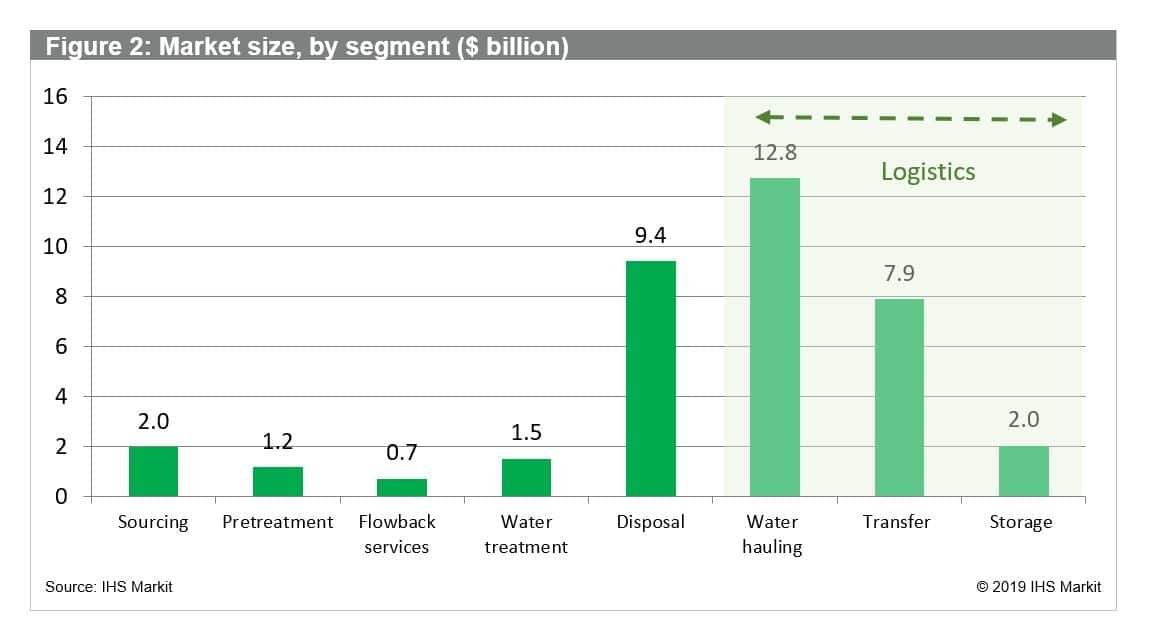

IHS Markit sub-divides the logistics market into hauling, transfer and storage. The market value of these activities is expected to be about $22.7 billion in 2019, with the Permian accounting for about 35% of that total; we expect the US market size to grow to $28.3 billion by the end of 2024, with the Permian accounting for nearly 42% of the total. Figure 2 shows our market size estimation by segment.

Figure 2: Market size, by segment ($ billion)

The accelerated growth in the Permian basin has generated a spike in disposal volumes. IHS Markit estimates that nearly 75% third-party disposal wells completed since 2016 are concentrated in the Delaware Basin (and 31% in Reeves County alone). This is still not adequate, and companies are responding to close the gap.

Due to the Permian’s importance on overall logistics market value, this is a good place to observe the leading edge of water management efforts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the challenges of managing produced water are like those recently faced when take-away capacity restricted oil production. Water transport is farther behind on the curve, and there is indeed ample room for cost reduction “simply” by changing from trucks to pipeline. The former has seen some cost savings thanks to better tracking technologies, but this no substitute transportation by pipeline, which never has to face traffic jams or a shortage of qualified drivers!

The pipelines will almost certainly come, and it’s interesting to see the strategies of these pipeline companies evolve in response to the highly dynamic Permian market. Absolutely, location is critical, as those organizations that can minimize their distance to both the field and treatment facilities have an off-the-bat advantage.

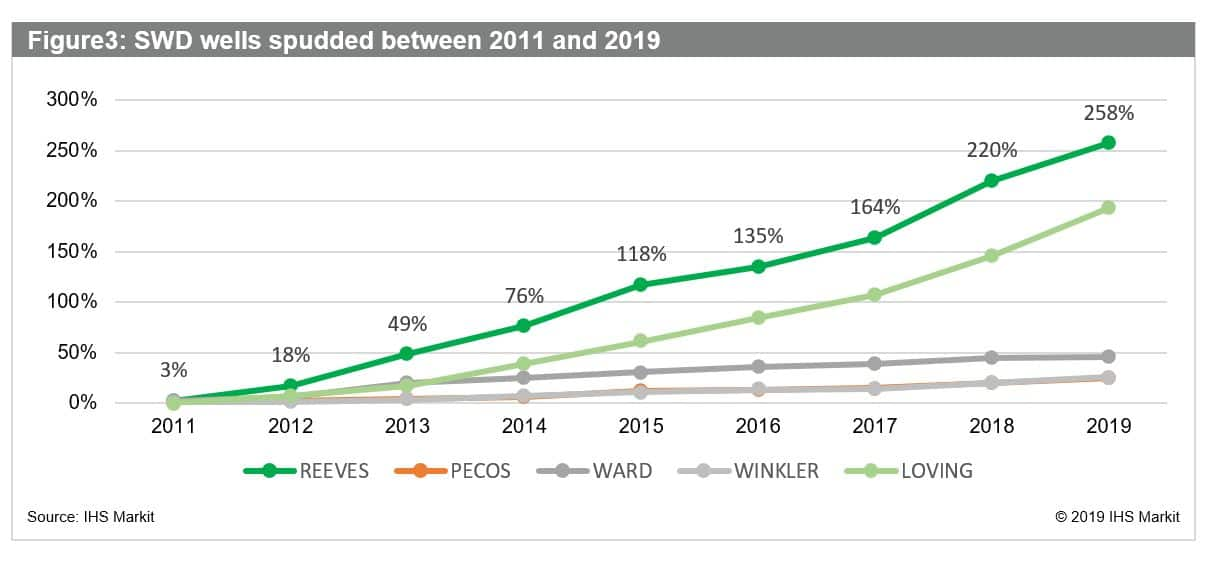

Of course, because Permian production is so diffuse, it’s not about all providers trying to secure an advantage in one location. Many third-party disposal firms have sought to focus on their own specific areas within the Permian, building out pipeline infrastructure between their disposal sites and nearby producing wells. This has led to the rise of localized oligopolies; for instance, NGL Water Solutions is heavily concentrated in the northern Delaware Basin along the New Mexico-Texas state line, while WaterBridge has focused almost entirely on the southern Delaware Basin in reeves County. In fact, Reeves county has more than doubled the numbers of salt-water disposal (SWD) wells spudded in the last 10 years, making it a perfect area for a localized oligopoly with minimal displacement between producing wells and disposal wells. Figure 3 shows SWD wells spudded increase in the last 10 years in Delaware.

Figure 3: SWD wells spudded between 2011 and 2019.

Most interestingly, we could see more collaboration – if only implicit – between companies. In fact, we expect to see more partnerships among operators with localized operations and a shift towards multi-operator infrastructure systems to handle oilfield water. Managing local resources will be highly relevant in this new “collaborative environment” to reduce operating cost associated with water.

The challenges in produced water go beyond just transportation itself. Water-collecting tanks are spread out and do not always fill at predictable or similar rates, so coordinating their emptying can turn into a complex optimization challenge: is it worth it to install remote tank monitoring? how much storage capacity should I send? what time of day should I empty my tanks, taking into account local traffic patterns? which treatment method is optimal given local regulations, cost constraints and volume requirements?

A further level of complexity is added when considering water recycling for fracking operations (we should specify that although this is a positive step, this is not the panacea some see, since produced water volumes dwarf frack water needs). Frac crews are expensive to keep on standby, and one operator at the recent Oilfield Water Industry Update water conference in Houston shared that sometimes they do need to wait on tanks to fill up for later use.

The undercurrent to all these issues is the need for centralized supply chain groups within service companies and operators, that are dedicated exclusively to water management, and establishing such capability will require two elements. First, an established record of best practices specific to each company’s location and operating areas will provide a foundation from which to operate. Second, this foundation should be leveraged by teams possessing a mix of relevant experience with the ability to translate their work histories into actionable, targeted initiatives. These are hard-to-find qualifications, highlighting yet one more difficulty in addressing the produced water challenges of the Permian.

Concluding Thoughts

The need for a set of robust logistics solutions is pushing the Permian water market to build and sustain a midstream water infrastructure – in equipment and expertise – in parallel to existing oil & gas pipelines. This is a critical development, since the combination of rising volumes and higher disposal costs threaten to shift up established cost curves, to the point where logistics costs could become the impediment to increasing or even just maintaining existing production.

The past decade’s surge in oil & gas production has created value for millions of people, allowing them to access domestic sources of energy at much lower prices than they would have otherwise under outdated “Peak Oil” scenarios. Unfortunately, the adage “there is no such thing as a free lunch” stands, and managing the Permian’s produced water is the key to maintaining the region’s status as a world-class oil producer.

Paola Perez Pena is a Principal Research Analyst, at IHS Markit.

David Vaucher is Associate Director, Research and Analysis at IHS Markit.

Posted 4 November 2019